Productivity | Dominik Mayer – Products, Asia, Productivity

How to Raise a Human

As part of NPR’s parenting series #HowToRaiseAHuman Michaeleen Doucleff visited a Maya village in Yucatán where even the youngest kids take great joy and pride in helping out in the house.

The Maya achieve this by letting the kids help whenever they want and however small the contribution is. In the beginning this takes longer than if the parents would do the task on their own.

Doucleeff writes:

The moms see it as an investment, Mejia-Arauz says: Encourage the messy, incompetent toddler who really wants to do the dishes now, and over time, he’ll turn into the competent 7-year-old who still wants to help.

Research supports this hypothesis, says the University of New Hampshire’s Andrew Coppens. “Early opportunities to collaborate with parents likely sets off a developmental trajectory that leads to children voluntarily helping and pitching in at home,” he says.

Or another way to look at it is: If you tell a child enough times, “No, you’re not involved in this chore,” eventually they will believe you.

Back in San Francisco Doucleeff tried it with her then two-year-old daughter:

So how did I turn a tantrum-fueled toddler into a chore-loving cherub (as if). To be honest, I needed to revamp the way I parent. I changed the way I interact with Rosy and the way I view her position in the family.

She made the chores the fun activity of the day, took her time doing them and included her daughter whenever possible.

For another article Doucleeff and colleague Jane Greenhalgh went to Iqaluit, Canada to learn how Inuit parents raise their kids to be calm adults that don’t get angry.

One part is not to yell:

“Shouting, ‘Think about what you just did. Go to your room!’ " Jaw says. “I disagree with that. That’s not how we teach our children. Instead you are just teaching children to run away.”

And you are teaching them to be angry, says clinical psychologist and author Laura Markham. “When we yell at a child — or even threaten with something like ‘I’m starting to get angry,’ we’re training the child to yell,” says Markham. “We’re training them to yell when they get upset and that yelling solves problems.”

Another one is storytelling:

For example, how do you teach kids to stay away from the ocean, where they could easily drown? Instead of yelling, “Don’t go near the water!” Jaw says Inuit parents take a pre-emptive approach and tell kids a special story about what’s inside the water. “It’s the sea monster,” Jaw says, with a giant pouch on its back just for little kids.

And one is role play:

When a child in the camp acted in anger — hit someone or had a tantrum — there was no punishment. Instead, the parents waited for the child to calm down and then, in a peaceful moment, did something that Shakespeare would understand all too well: They put on a drama. (As the Bard once wrote, “the play’s the thing wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.”)

“The idea is to give the child experiences that will lead the child to develop rational thinking,” Briggs told the CBC in 2011.

In a nutshell, the parent would act out what happened when the child misbehaved, including the real-life consequences of that behavior.

All three articles are highly recommended.

Hire Less

Basecamp in Getting Real:

Don’t hire people. Look for another way. Is the work that’s burdening you really necessary? What if you just don’t do it? Can you solve the problem with a slice of software or a change of practice instead?

Whenever Jack Welch, former CEO of GE, used to fire someone, he didn’t immediately hire a replacement. He wanted to see how long he could get along without that person and that position.

I genuinely believe that with the right processes and the right people most companies need only half their headcount.

The Value of Ignorance

The American Management Association published an excerpt from William A. Cohen’s book A Class with Drucker:

“I never ask these questions or approach these assignments based on my knowledge and experience in these industries,” answered Drucker. “It is exactly the opposite. I do not use my knowledge and experience at all. I bring my ignorance to the situation. Ignorance is the most important component for helping others to solve any problem in any industry.”

Hands shot up around the room, but Drucker waved them off. “Ignorance is not such a bad thing if one knows how to use it,” he continued, “and all managers must learn how to do this. You must frequently approach problems with your ignorance; not what you think you know from past experience, because not infrequently, what you think you know is wrong.”

Cohen continues with a story about Americans building British cargo ships during World War II without having any knowledge about building ships.

This reminds me a lot of John Ramsay, the designer of the Limiting Factor, the “first commercially certified full ocean depth manned submersible” (Wikipedia), portrayed in The New Yorker:

Ramsay, who works out of a spare bedroom in the wilds of southwest England, has never read a book about submarines. “You would just end up totally tainted in the way you think,” he said. “I just work out what it’s got to do, and then come up with a solution to it.”

Elon Musk, quoted in one of Tim Urban’s amazing articles:

I think generally people’s thinking process is too bound by convention or analogy to prior experiences. It’s rare that people try to think of something on a first principles basis. They’ll say, “We’ll do that because it’s always been done that way.” Or they’ll not do it because “Well, nobody’s ever done that, so it must not be good.” But that’s just a ridiculous way to think. You have to build up the reasoning from the ground up—“from the first principles” is the phrase that’s used in physics. You look at the fundamentals and construct your reasoning from that, and then you see if you have a conclusion that works or doesn’t work, and it may or may not be different from what people have done in the past.

68 Bits of Unsolicited Advice

Kevin Kelly:

It’s my birthday. I’m 68. I feel like pulling up a rocking chair and dispensing advice to the young ‘uns. Here are 68 pithy bits of unsolicited advice which I offer as my birthday present to all of you.

Great list. Some of the bits I like particularly:

- Being able to listen well is a superpower. While listening to someone you love keep asking them “Is there more?”, until there is no more.

- If you are looking for something in your house, and you finally find it, when you’re done with it, don’t put it back where you found it. Put it back where you first looked for it.

- Before you are old, attend as many funerals as you can bear, and listen. Nobody talks about the departed’s achievements. The only thing people will remember is what kind of person you were while you were achieving.

–– James Baldwin

How to Fix a Broken Knee

In case you’re ever hit by another motorbike and break your tibial plateau, that’s what they’re gonna do. Just saying…

–– James Clear

Privacy at Apple

Former Apple engineer David Shayer explains on TidBITS why he trusts Apple’s new exposure notification. He touches the internal processes that prevent excessive user tracking:

Once I had recorded how many times the Weather and Stocks apps were launched, I set up Apple’s internal framework for reporting data back to the company. My first revelation was that the framework strongly encouraged you to transmit back numbers, not strings (words). By not reporting strings, your code can’t inadvertently record the user’s name or email address. You’re specifically warned not to record file paths, which can include the user’s name (such as

/Users/David/Documents/MySpreadsheet.numbers). You also aren’t allowed to play tricks like encoding letters as numbers to send back strings (like A=65, B=66, etc.)Next, I learned I couldn’t check my code into Apple’s source control system until the privacy review committee had inspected and approved it. This wasn’t as daunting as it sounds. A few senior engineers wanted a written justification for the data I was recording and for the business purpose. They also reviewed my code to make sure I wasn’t accidentally recording more than intended.

Read the whole thing. It’s fascinating.

Five Steps to Your Ideas

Chuck Frey on The Sweet Setup:

Like many things in business, creativity responds well to a process — one that guides you along the path of birthing, nurturing and implementing game-changing ideas. This simple system includes 5 steps:

Investigate → Generate → Incubate → Evaluate → Activate

It never ceases to amaze me how all these techniques can be expressed as ways through the Munich Procedural Model of product development.

Gell-Mann Amnesia

Michael Crichton in his talk Why Speculate? given at the International Leadership Forum:

Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray’s case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Paper’s full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.

The Design Squiggle

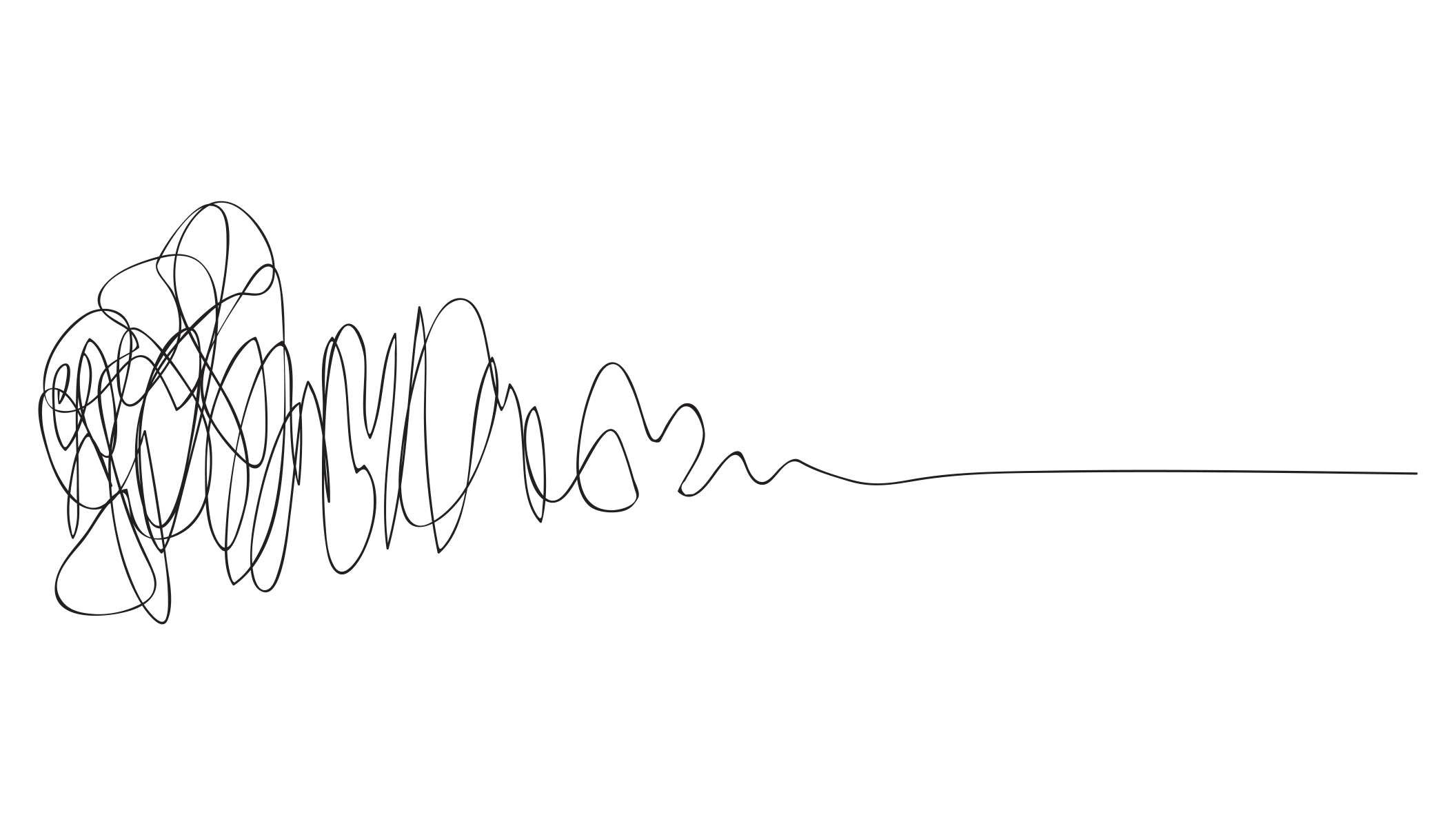

Damien Newman created a squiggle to symbolizes the design process from research on the left via concept and prototyping in the middle to the final design on the right.

The Process of Design Squiggle by Damien Newman, thedesignsquiggle.com

–– Georg Christoph Lichtenberg?

Cities and Ambition

Paul Graham in a 2008 essay:

Great cities attract ambitious people. You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder.

The surprising thing is how different these messages can be. New York tells you, above all: you should make more money. There are other messages too, of course. You should be hipper. You should be better looking. But the clearest message is that you should be richer.

What I like about Boston (or rather Cambridge) is that the message there is: you should be smarter. You really should get around to reading all those books you’ve been meaning to.

When you ask what message a city sends, you sometimes get surprising answers. As much as they respect brains in Silicon Valley, the message the Valley sends is: you should be more powerful.

Read the whole essay. It’s a very thought provoking. What does Munich tell you, what Shanghai, what Saigon?

Fast Software

Craig Mod:

I love fast software. That is, software speedy both in function and interface. Software with minimal to no lag between wanting to activate or manipulate something and the thing happening. Lightness.

Software that’s speedy usually means it’s focused. Like a good tool, it often means that it’s simple, but that’s not necessarily true. Speed in software is probably the most valuable, least valued asset. To me, speedy software is the difference between an application smoothly integrating into your life, and one called upon with great reluctance. Fastness in software is like great margins in a book — makes you smile without necessarily knowing why.

John Gruber comments:

One of the confounding aspects of software today is that our computers are literally hundreds — maybe even a thousand — times faster than the ones we used 20 years ago, but some simple tasks take longer now than they did then.

Too few product managers treat speed as a feature. There should be tests that make sure software stays fast (or becomes faster) when new features are addede.

Hugo, which is powering this site, is a positive example, advertising itself as “the world’s fastest framework for building websites”.

Lead developer Bjørn Erik Pedersen said in an interview with the New Dynamic:

I try to play the zero-sum game when adding new features: The processing time added by the new feature will have to be compensated by improvements in others […].

Performance bottlenecks show up in the most surprising places, so you have to benchmark. Performance gains and losses come from smaller accumulated changes over time. And speed matters. Try Hugo’s server with livereload and you will see.

How to Protect a President

Former Secret Service Agent Jonathan Wackrow, now managing director at Teneo Risk, explains how the Service protects the President and other VIPs.

Interesting to hear what they’re looking at regarding venues. I never thought about threats coming from air conditioning or light access.